Two weeks ago, while taking a walk well past nightfall, I came around a bend in the road, now fully in the dark due to the removal of the streetlight for road construction. Streetlights don’t exist in most parts in my new home country, but they are scattered throughout my neighborhood.

I took little notice of two men sitting on their motorcycle there in the darkness. Though I didn’t know it at the time, they were waiting for me. I didn’t see what was coming next. One guy came behind me and grabbed me, while the other came at me from the front.

In my naiveté, I didn’t think I was being robbed. All I knew is that I was being attacked. I have lived in Kenya for months now, walking just about everywhere I go, and feel safe. Not because I don’t do things that most would consider somewhere between stupid and irresponsible, but because I pay very close attention. I keep enough distance when the the situation feels threatening to be able to think, react and preempt. But here I was, in my nice Nakuru neighborhood, with all my defenses down, lost in thought.

If I had known they wanted my phone, I probably would have either given it to them, or at least tried my hand at a conversation. I might have gotten the first footage for the movie I have been wanting to make – letting an older iPhone get stolen with a note on the back saying: film for a day and I’ll give you $20 for the footage and my phone back. Unfortunately, all I knew was that I was being attacked. And I fought back.

When all was said and done, I had cuts, welts and bruises all over; I lost the naive feeling of total safety in my neighborhood, lost my phone, some blood and some sleep that night, while getting checked at the hospital. I’ll spare you the photos, but if you’re curious, I have pictures on my Instagram.

But none of that is the tragedy of this story. Probably for more reasons than I can think of. The tragedy in this is that, in our dangerous world, there are so many men who feel that this is the best way for them to get money to survive. This kind of crime is ultimately an act of desperation, or at very least, it starts that way. In fact, there is desperation in so much violence and crime – desperation in not knowing another way to get their basic human needs met.

If you’ve ever had an emotional outburst, then later regretted “losing your cool,” it’s not that you didn’t know there’s a better way, but you felt desperate or didn’t know what else to do in that moment. Often, it feels as if something is in the driver’s seat. It’s easy to justify our own desperate behavior because when I act or react out of desperation, I KNOW that I was in a place where I could see no other way.

At points in our lives, we’re pushed off our center. We act or react in ways we often wish we didn’t. And the reality for most of us, it is rarely a matter of survival. But for those for whom it is, it can be the difference between eating or not, paying rent or being homeless. Those people will resort to greater extremes. Like, beating up a dude who looks like he has something worth stealing.

This stuff happens everywhere. There is nowhere where in the world where anyone is fully safe from this reality. We live in a world with huge inequality. Because of that, there are people who will take whatever they can get, however they can get it.

Additionally, gender inequality puts a burden on men to be “real men” and to provide. When they can’t, they may end up in all sorts of compromised positions, including the positions of the men who jumped me.

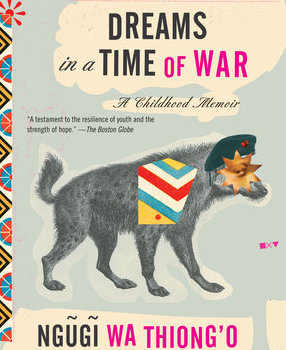

In his memoir Dreams in a Time of War, Ngugi wa Thiong’o writes of growing up in Kenya pre-independence, in a time still when most Kenyans didn’t have money. Money simply wasn’t a thing, a fact exploited by the British in devastating ways.

The British came to Kenya, moved into the best parts of the country and made sure no blacks could live there, displacing thousands of peoples from their homes. They then forced anyone who still had property to pay taxes. Without money, the locals had no choice but to forfeit their ancestral lands and/or go work for the British, for whatever wages the colonials would pay, in order to make money to pay taxes.

These policies, among others, split families apart. Men had to go work on white farms, leaving the women alone, and their children without fathers. Other times, the women had to work as domestics (at best) or prostitutes (at worst)- whatever they could do to make money to pay those taxes and survive in a world that now required money. If they couldn’t pay the taxes, they lost their land… and ended up in the same fate: no way to feed themselves or their families without land to grow food. Here they were again, at the mercy of white employers.

The residuals of this desperation still exists – men without land to grow food. Some turn to honest work, often being exploited for paltry wages, others to violence.

Over the years, the Global North has continued to siphon off resources, leaving local populations in poor shape. I have to take responsibility that much of my comfort, and even the affordability of the phone that was stolen, is due in large part to this global inequality.

When Kenya’s President asked voters not to hold him accountable for the “sins of my father,” he failed to realize that, as long as he both benefits from those sins, nor actively engages in rectifying them, then he certainly MUST be held accountable. I, too, benefit from the sins of my fathers. If I don’t want to be judged by those sins, I need to work towards healing the wounds they caused.

That night at the hospital, my good fortune was staring me in the face. I could afford to get medical care, where I was given respect and treated with dignity. I had friends who drove me there. Earlier in the day, I did work I love, and would do the same as soon as my wounds healed. I have amazing children and a life partner more magical than I ever could have ever imagined. And when all was said and done, my wounds cleaned and bandaged, I was home, laying on a comfortable mattress.

I there’s so much I can and must do to heal those old, yet fresh, wounds of injustice. I’ll start with asking their forgiveness and offering mine. I will be curious about the events of that night in my life. I will take those lessons so that I can make the world more loving and caring for it, and not the other way around.